Part 3: Bottling, Malting, Saloons and Depots

This is the third of four articles that focus on the American Brewers' Review 1898 Brewers' Guide.

Introduction: American Brewers' Review 1898 Brewers' Guide

Part 1. An overview of the Brewers' Guide with production figures mapped

Part 2. A discussion of the types of beer brewed in 1898

Part 4: Germans in the brewing industry in 1898

By 1898, the brewing industry in the United States had been slowly adopting bottling technology and pasteurization for over a decade. The vast majority of beer though was still sold in wooden barrels. A few brewers, Pabst and Anheuser-Busch among them, had started trying to expand their market by selling bottled beer shipped away from their home markets by railroad. At the turn of the century their success was still limited. Most brewers at that time expanded markets by opening saloons or exerting control of saloons through lending arrangements. Saloon keepers and brewers competed in a market increasingly saturated with industrial produced beer. They offered incentives like free lunches to gain customers. A free lunch in a saloon with a few cups of beer became a daily routine for many industrial workers. Saloons offered free meeting space to urban politicians and unions. They became general purpose gathering places in neighborhoods. Their association with machine politics, organized labor, and work-day drinking all contributed to the passage of national prohibition. Saloons were places for men only. Women were almost never allowed in them except occasionally in special back rooms.

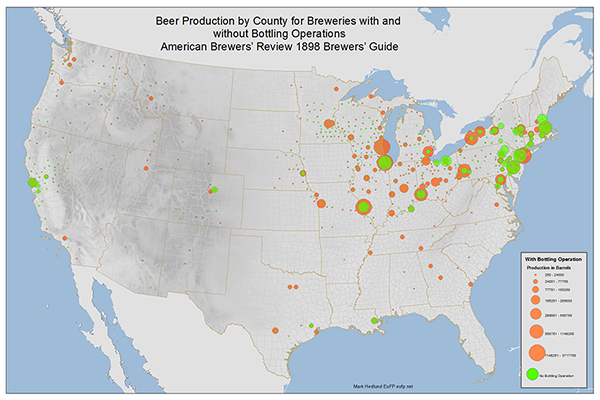

In 1898, the brewing industry was still slowly adopting bottling. Bottling equipment was a popular topic in the two main trade journals: The Western Brewer, and American Brewer’s Review. 877 breweries reported selling bottled beer in the 1898 Brewers' Guide; 843 did not.

Click image for larger version.

In the map above, the production of all breweries that had bottling operations in a given county are added together and symbolized with red circles. All production in establishments without, is totaled and shown in green. All of the major brewers in Milwaukee had bottling plants by 1898. About half of those in Chicago did. In St. Louis, Anheuser-Busch, and Lemp had bottling plants but many of the smaller breweries did not. Many very small breweries in the west sold bottled beer, presumably, so that customers could carry purchases away for long distances. Breweries in northeastern urban centers were less likely to have bottling plants. Bottled beer was still an unproven market and it required expensive equipment. Men in the industrial cities of the northeast came home from the saloons drunk. They did not drink beer at home. The largest brewery in the country that did not sell bottled beer was Hell Gate in Manhattan which produced 550,000 barrels in 1898. The next largest were Ballantine in Newark New Jersey and the Lion Brewery in Manhattan, both producing 450,000 barrels. Pabst in Milwaukee was the largest brewery with a bottling plant. Pabst produced about a million barrels in 1898 but only a small portion of that was bottled.

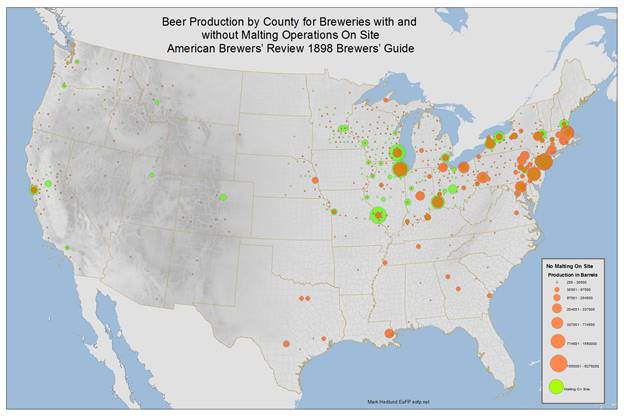

Malted barley is the main ingredient in beer aside from water. Malting requires sprouting barley grains by wetting them and then baking the sprouted grain to stop growth. Malting the quantities of barley industrial breweries used required specialized malting buildings and expensive equipment. Buildings for malting were massive, often windowless, structures called malt houses. Malt houses were one of a few special purpose buildings typically found in larger brewery campuses. In many cases they are the only surviving structures of a brewery because they were easily adapted for use as cold storage warehouses after prohibition. But many breweries made the decision to purchase malted barley rather than make it themselves. This was especially true in urban areas where space for extra buildings was expensive. The 1898 Brewer’s Guide also includes a guide to maltsters, as specialist malt producers were called. I did not map that part of the guide. In 1898, 557 breweries were producing their own malt and 1,163 were not.

Click image for larger version.

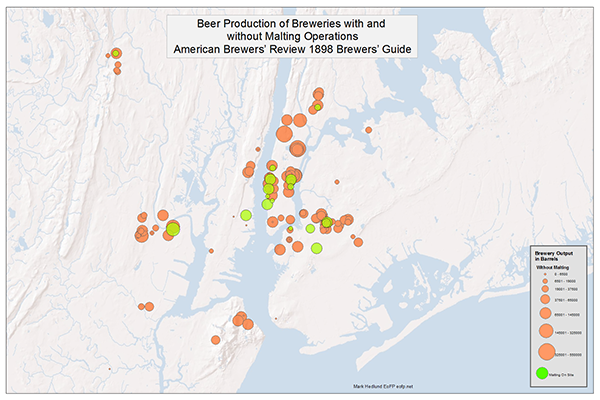

The map above was made with same technique of aggregating brewery production by county as the bottling map. It produces a similar result. Breweries in the crowded urban centers of the northeast were less likely to produce their own malt than breweries in the Midwest and west. Breweries in the south didn’t produce malt, likely because of climate. Malt houses needed to be kept cool and though mechanical refrigeration was available, it was expensive. The map of the New York Area below shows the actual locations of breweries, if known. There aren’t many apparent patterns in where breweries decided to purchase malted grains and where they malted their own. It is worth noting that many of the breweries making their own malt in the New York area produced ale and porter. I’m not sure if this was because malt suitable for ale and porter was harder to find than malt for lager, but it seems possible.

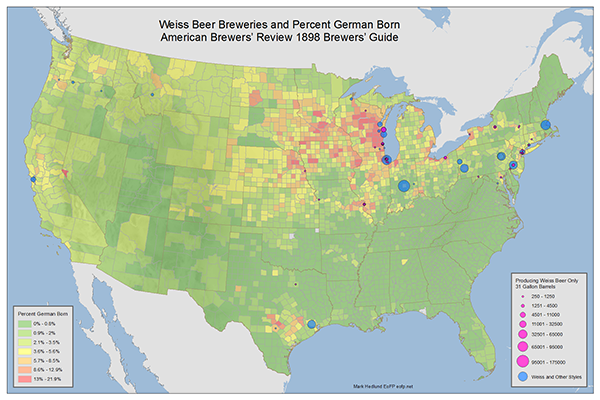

The 1898 Brewers Guide indicated what styles of beer a brewery produced. Breweries that made ale, porter and lager were discussed earlier. Weiss beer was also made in 90 breweries. Weiss beer is a traditional German style of beer made with wheat rather than barley. 60 of the 90 breweries producing Weiss beer only produced Weiss beer. All of those 60 breweries sold bottled beer. This suggests to me that the Weiss beer business was a specialized boutique industry. The largest brewery producing only Weiss beer was Schreihart Brewing Co in Manitowoc Wisconsin which produced 6,500 barrels. Certain types of Weiss beer are associated with certain regions of Germany. But the Brewer’s Guide doesn’t clarify which styles were produced. Berlin style Weiss beer is mentioned in a few business names. No clear patterns emerge from the map below which shows Weiss beer breweries and the percent of population born in Germany. Some larger breweries that reported making Wiess beer, as well as other styles, like Suffolk Brewing in Boston, probably didn’t make very much Wiess beer, mostly producing other styles.

As I mentioned earlier, saloons were the primary sales channel for breweries in 1898. Owners of breweries often lent money to saloon owners or to prospective saloon owners in exchange for exclusive sales arrangements. Some smaller breweries served beer in adjacent beer gardens or dance halls. Most of the larger industrial breweries did not. Larger expansion minded brewers like Pabst built and operated many dozens of branded saloons which were designed to evoke the architecture of the parent brewery. Some branded saloons were built across state lines from their parent breweries but most were within the same metropolitan region.

The Pabst Saloon above in Racine Wisconsin was built with the same cream colored brick and similar castle like Romanesque ornamentation as the Pabst brewery in Milwaukee.

Larger brewing companies built elaborate distribution systems with dozens of depots connected by rail. Most of these brewers' depots were within a hundred or so miles of their parent breweries. Some were more distant. In some cases the brewing company employed the same architectural signifiers on beer depots as they employed on their breweries, offices, and branded saloons. The brewers used architectural ornamentation as brand building advertisement. Romanesque like styles were most frequently employed. The structures were meant to evoke traditional Bavarian buildings such as castles and churches. They did not much resemble the breweries or other industrial buildings being constructed in Bavaria and Bohemia at that time. The saloons and depots expanded the material footprint of the brewing industry into the urban fabric of cities throughout the country. Breweries became intertwined in the cultural and political fabric of urban America as well via organized labor, the fight against women's suffrage and political organizations.

Anheuser-Busch beer depot in Quincy Illinois

Part 4: Germans in the brewing industry in 1898

All content on these pages Copyright Mark Hedlund 2012-2019. All rights reserved. Use in school projects and with links on social media is always okay. Please send me an email to request permission for any other use: hedlunch@yahoo.com Non-exclusive commercial publication rights for most photos is $25 per image.